By Joaquin Salinas

In 1914, four decades before Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka and approximately three decades before Mendez v. Westminster School District of Orange County, a court ruling in the town of Alamosa, Colorado favored a lawsuit filed by Francisco Maestas and other Hispano families against the superintendent of Alamosa School District, George H. Shone, and other school board members over the segregation and discrimination that Mexican-American students faced in schools. This ruling, later known as the Francisco Maestas et al. vs George H. Shone et al., is one of the United States’ first successful school desegregation cases, and the earliest known case to involve Mexican-Americans.

With the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the Mexican-American War came to an end on February 2, 1848, after a two year conflict that began with a land dispute over the territory of Tejas (Britannica 2023). The United States, being the victor of this war, annexed Tejas as well as several other territories which would become the states of Arizona, California, western Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming.

Aware of the Mexican residents already living in these territories, the United States government addressed the issue of citizenship for these people who watched as the border crossed them by stating in Article IX of the treaty that: “[t]he Mexicans who…shall not preserve the character of citizens of the Mexican Republic…shall be incorporated into the Union of the United States and be admitted, at the proper time…to the enjoyment of all rights of citizens of the United States according to principles of the Constitution,” (Johnson, 2000).

This, along with other promises made by the United States government were never fulfilled, as contradictions immediately arose as the sentiment expressed by American citizens who migrated to these newly acquired territories reflected racist attitudes that discriminated against the Mexican settlers. This remained true even for what historian Richard Nostrand referred to as the Hispano Homeland: the San Luis Valley (Donato et al., 2016).

Settled on Indigenous land that once belonged to Puebloan cultures as well as the Apache, Diné, Uté, and other Indigenous peoples, the Hispanos of the San Luis Valley was described by the Rocky Mountain News as: “…New Mexicans; a mongrel race, half Spanish and half Indian,” (Katie Dokson, 2022).

As Hispanos in this area continued to face discriminatory treatment, this resulted in creation of mutual aid societies that sought to use community support to fight against the racist conditions in which they lived under (Dokson, 2022). Of these include La Sociedad Protección Mutua de Trabajadores Unidos (SPMDTU), an organization founded in the town of Antonito, Colorado in 1900; only thirty miles south of where the Maestas Case takes place: Alamosa, Colorado (Dokson, 2022).

Located in what is considered to be the commercial center of the San Luis Valley, the Hispanos of Alamosa, like many others, found themselves the targets of discriminatory action(s) by Anglo migrants that would later be coined by Salvadorian journalist Roberto Lovato as “Juan Crow.”

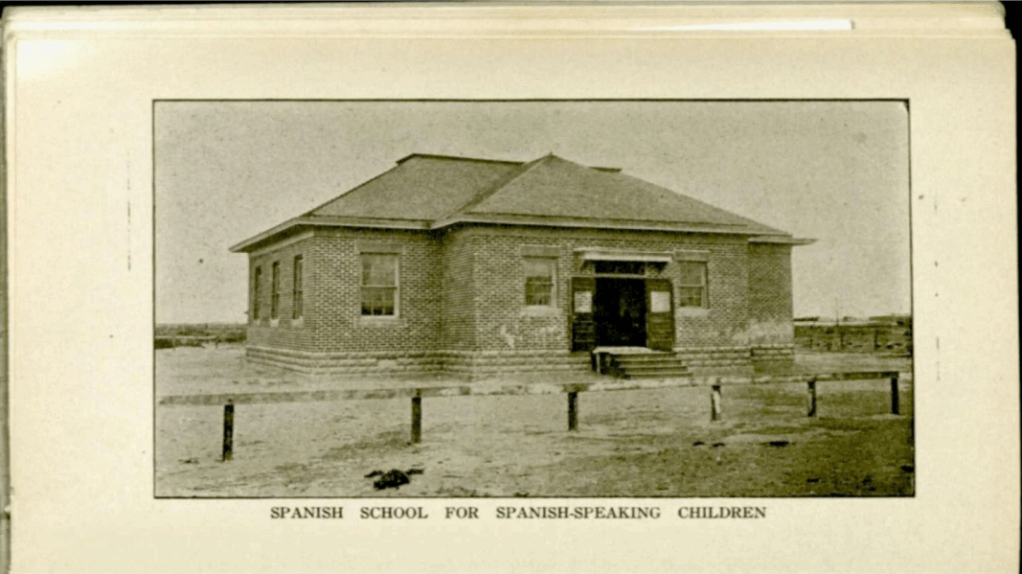

This includes, in 1909, the Alamosa School Board purchasing land on the south side of town, also known as the Mexican side of town, to construct a “Mexican school”. The initial purpose of this school was to assimilate Spanish-speaking students more easily into the English-medium school system by providing language support (Dokson, 2022). The school itself was described to be a modest building with four classrooms that staffed three teachers and held approximately 140 Mexican-American students (Donato, et al., 2016). Once it was completed, it drew a great amount of local attention with one newspaper editor in Creede, Colorado, even reporting: “Back east and south they build separate schools for negro children. At Alamosa, they have just built one exclusively for Spanish children,” (Donato, etc al,. 2016). Then, the Alamosa School Board would alter this policy on February 5, 1912, by enacting a new policy that demanded that any students with a Spanish surname must attend the Mexican school, regardless of their English proficiency (Dokson, 2022).

The reaction to this policy change by Hispano parents, who, along with their children, were constitutionally considered United States citizens, was that they viewed it as racial discrimination. They believed that language was entirely being used as an excuse to segregate Mexican-American children while race was the actual reason behind the school’s actions, (Dokson, 2022). Because of this, the parents immediately filed a complaint to challenge if the school board had the authority to segregate Mexican-Americans students (Donato, etc al 2016).

Nonetheless, despite the policy, Hispano parents attempted to enroll their children in the English speaking school but were ultimately denied (Dokson, 2022). This was the first of many appeals and objections that the Mexican-American community would experience against the Alamosa School District, and its superintendent, George H. Shone. They also appealed to Alamosa School Board of Education, the Colorado State Superintendent of Instruction, and the Colorado State Attorney General, but they proved to be unable or unwilling to address the unfairness of the policy change (Donato, etc al 2016).

In response, during the fall of 1913, Mexican-American families staged a walkout and refused to send their children into the Mexican school (Donato et al. 2016). This effort however, proved to be unsuccessful. School officials were quoted as saying: “…let the children go without education,” (Donato el all, 2016), while also accusing the parents of neglecting their children’s schooling (Dokson, 2022).

During this period, the Spanish American Union, a support organization formed in 1912, consulted with local lawyers in an attempt to file a lawsuit challenging the Alamosa School District in court (Donato el all, 2016). However, they were unable to find suitable representation, as several lawyers persuaded Hispano families not to pursue a lawsuit, arguing that it would not only be unwinnable, but expensive (Dokson, 2022).

This would change, as a former teacher at the Mexican school, J. R. C. Ruybal, would become a writer for an unnamed Spanish American newspaper, wrote an article asking for other communities in the San Luis Valley for their support, and funding to file the aforementioned lawsuit (Donateo et al., 2016). Once money was raised, a second committee was formed, made of ten members, to focus on securing legal counsel (Dokson, 2022). Among these members included a Catholic Priest by the name of Father Montell, who suggested that the committee should hire a young man, named Raymond Sullivan, from Denver, who would represent them at a very reasonable price (Dokson, 2022). Following this suggestion made by the Father an agreement was made. Mr. Sullivan would represent several Mexican-American families from Alamosa, and would only charge them two hundred dollars, plus expenses (Dokson, 2022). And so, a man by the name of Francisco Maestas was selected as the lead plaintiff, and the lawsuit began.

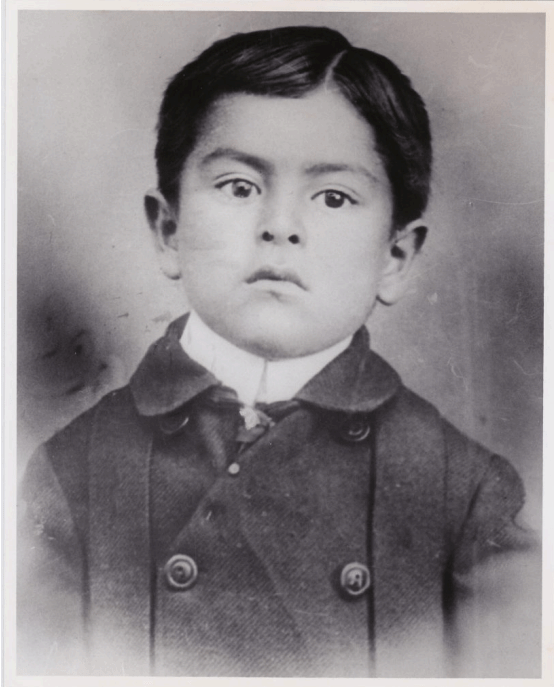

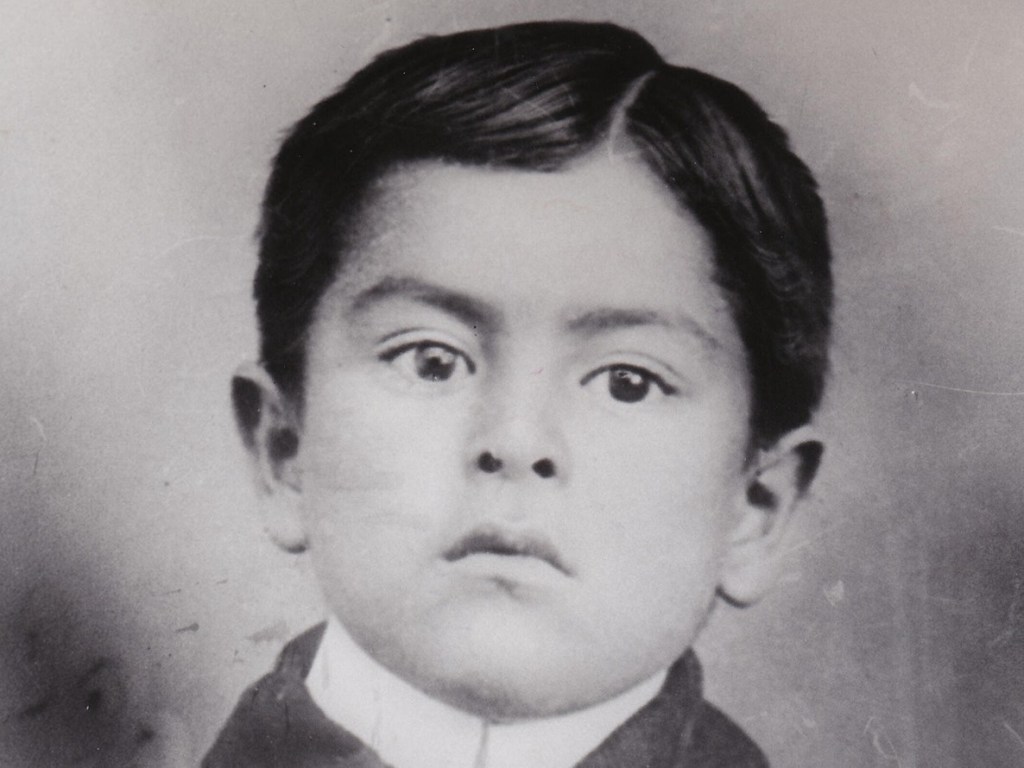

Although there was no transcript of the trial, we know what occurred because of court records and newspaper accounts (Donato et al., 2016). In 1913, Raymond Sullivan filed the lawsuit on the behalf of several Mexican-American families. Francisco Maestas was selected as the lead plaintiff because of the particular injustices his 11 year old son, Miguel, experienced was especially severe (Dokson, 2022) This includes crossing several dangerous rail roads to attend the Mexican school, on the south side of town, instead of the White school, on the north side of town, where he actually lived (Dokson, 2022).

Francisco, being a railroad foreman, knew how dangerous it was for his son to be constantly crossing and recrossing these tracks, and attempted to enroll him into the aforementioned white school (Donato et al., 2016). However, on September 2, 1913, in a meeting with the school superintendent, George O. Thompson, he was refused and instead directed that Miguel will continue attending the Mexican school (Donato et al., 2016). This refusal to admission was common to other Mexican-American families who lived closer to the north side school. In fact, school board officials stated that “all children of Mexican descent would be confined to the Mexican school up to the 5th grade,” (Donato et al., 2016).

Sullivan would argue against this by stating that because the school wasn’t allowing children to attend the school closest to them, i.e. the white school, that school officials were making a “…distinction and classification of pupils in the public schools on account of race or color contrary to Article IX, Section 8 of the Colorado Constitution…” (Dokson, 2022). He then called the court to the school board to “admit the said child of plaintiff to the North Side School or the most convenient of the public schools of said city to which he has the right of admission without any distinction or classification on account of his race or color,” (Dokson, 2022). The refusal to allow Mexican-American children to attend the school closest to them became the driving force behind Sullivan’s argument.

Believing that Sullivan made a sufficient case, District Court Judge Charles Holbrook, issued an order to the Alamosa School Board to either allow the Mexican-American children to attend the most convenient public school, or to file an answer arguing why they shouldn’t (Donato et al., 2016). Upon hearing this, the school board chose to file an answer.

In this answer, John T. Adams, the representative who spoke on the behalf of the Alamosa School Board, recognized what was said regarding Miguel’s refusal of enrollment as true, while also challenging several points of Sullivan’s argument (Donato et al., 2016).

First, Adams argued that Miguel Maestas, and the other Mexican-American students were not segregated due to their race as the children were actually caucasian. He stated that: “… all the children of said school district are of the same race and color, to-wit, white children of the Caucasian race, with the exception of a few negroes,” (Donato et all., 2016).

Second, Adams explained that the reason why Miguel was denied admission to the north side school was because of his impaired ability to speak English and was academically unprepared (Donato et all., 2016). He pointed to the fact that Miguel had failed an English exam, and was behind academically because his parents took him out of school for three months (Donato et al., 2016). The reasons behind this being the walkouts of 1912.

Thirdly, when speaking about the dangers that Miguel had to go through in order to attend Mexican school, Adams stated that there were warning signs and signals put in place by railroad companies to keep pedestrians like Miguel safe (Donato et al., 2016). He argued that it was no more dangerous than crossing the street (Donato et al., 2016).

Finally, Adams argued that the segregation of all students was important for the sake of education itself. He claimed that it was “… impossible to efficiently teach the non-speaking children in said school district, in English grammar, or any other subject, without seriously retarding and impairing the educational advancement and development of the school children of said city,” (Donato et al., 2016). It would result in great injury and loss to the school district and tax payers (Donato et al., 2016).

Adams then closed his argument by stating that the defense believes that the lawsuit was filed by individuals who didn’t have children in the school district, didn’t pay taxes in the district, individuals who were of Mexican birth, and individuals who wanted to embarrass and discredit the school district for personal reasons (Donato et al., 2016). The Mexican-American students’ inability to speak English became the driving force of Adams and the Alamosa School Board’s argument for why schools had to stay segregated.

Sullivan was able to see through this argument, and was prepared to give a rebuttal by having Mexican-American children testify in court to display their proficiency in English. This, of course, included Miguel, who was called to the stand and reported as being “timid and abashed by the reason of the crowded court room,” (Donato et al., 2016). Despite this outward shyness, Miguel was able to understand and answer all the questions asked by Sullivan in English (Donato et al. 2016). Then, during Adams’ cross examination, he tried to do so through the use of an interpreter (Donato et al. 2016). This proved to be pointless as Miguel “responded in English before the interpreter could finish the questions,” (Donato et al. 2016). Before leaving the stand, Migual told the court he was often late to school because of waiting for trains to pass (Donato et al. 2016). Other children that testified in court showed proficiency in English as well (Donato et al. 2016).

Finally, in March of 1914, District Court Judges Charles Holbrook wrote in favor of Francisco Maestas and the other Mexican-American families of Alamosa, Colorado. Judge Holbrook was convinced that school officials had rationalized the English deficiency and academic inaccuracy of some Mexican-American students, as a reason to send all of them to Mexican school (Donato et al. 2016). He also understood why “Spanish speaking people believe that their children are excluded from the two English speaking schools, upon account of race,” (Donato et al. 2016). In his ruling Judge Holbrook stated: “in the opinion of the court … the only way to destroy this feeling of discontent and bitterness which has recently grown up, is to allow all children so prepared, to attend the school nearest them,” (Donato et al. 2016).

The Mexican-American community had won, but not without total victory. Bringing a bittersweet end to the Maestas Case, District Court Judges Charles Holbrook added a stipulation in his ruling that any child not proficient in English was to remain at the Mexican school (Donato et al. 2016). This essentially means that the school officials were still able to keep non-English speaking students in the Mexican school (Donato et al. 2016). The Maestas Case was finally closed on April 17, 1914.

Thank you for reading. The Maestas Case was only recently discovered as early as 2013 by the efforts of Dr. Gonzalo Guzmán, Dr. Rúben Donato, and Dr. Jarrod Hanson, with additional assistance from Martín Gonzales, the retired 12th Judicial District Judge of Alamosa, Colorado. This history, OUR* history, embodies the ideologies so deeply rooted in the United States that it would be a crime in itself to dismiss, or forget it. As the world continues to spin around, it is important that we remember the efforts of our predecessors so we remain determined in our everlasting struggle for truth, justice, and liberty. REMEMBER FRANCISCO MAESTAS. REMEMBER MIGUEL MAESTAS. C/S.

Works Cited

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo”.

Encyclopedia Britannica, 7 Feb. 2024,

https://www.britannica.com/event/Treaty-of-Guadalupe-Hidalgo. Accessed 13

March 2024.

Dokson, Katie. “An Almost-Forgotten Fight for School Desegregation.” An

Almost-Forgotten Fight for School Desegregation | History Colorado, History

Colorado, 13 Sept. 2022,

http://www.historycolorado.org/story/2022/09/13/almost-forgotten-fight-school-des

egregation.

Donato, R., Guzmán, G., & Hanson, J. (2016). Francisco Maestas et al. v. George H.

Shone et al.: Mexican American Resistance to School Segregation in the

Hispano Homeland, 1912–1914. Journal of Latinos and Education, 16(1),

3–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348431.2016.1179190

“Immigration, Citizenship, and U.S./Mexico Relations: The Tale of Two Treaties.”

BILINGUAL REVIEW, vol. 25, no. 1, Jan. 2000, pp. 23–38. EBSCOhost,

research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=23377203-9cc4-3fc5-ac91-81396

d7d58a2.

Leave a comment